B S Dara

As an NRI returning to my beloved Jammu this year after a long interlude abroad, I found myself deeply pleased to witness the visible transformation of my hometown. The streets gleamed, public spaces looked cleaner, and the ambitious Smart City initiative had clearly begun reimagining Jammu’s urban landscape. Let me say it plainly that Jammu is transforming.

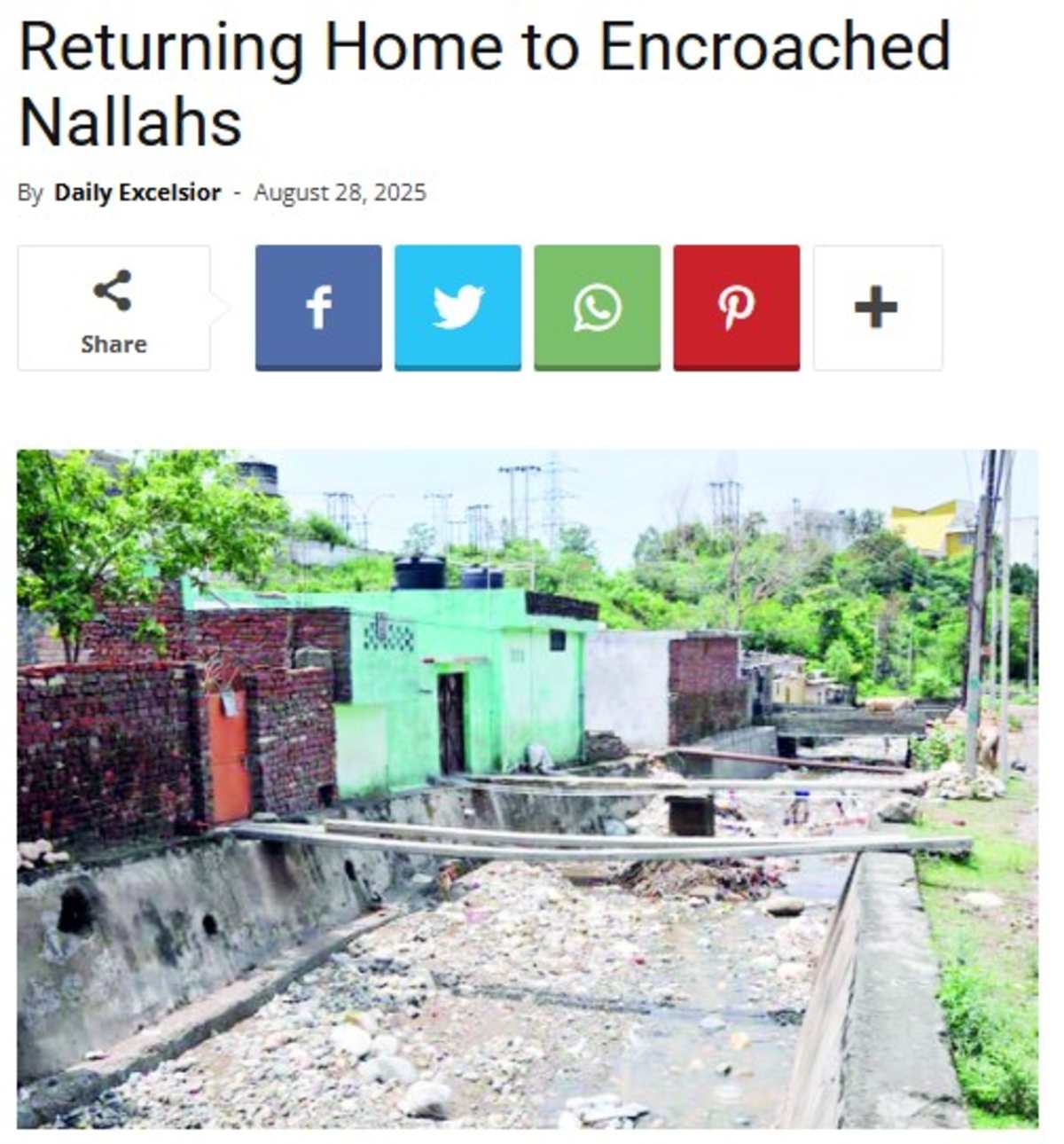

The city’s facelift is real and, in many parts, commendable. Roads gleam under LED lights. Green belts now split traffic like arteries of hope. Public spaces are cleaner, well-marked, and inviting. There are upgraded drainage systems on paper, e-rickshaws running on solar, and weekly garbage pick-ups, initiatives that show intent. Records show that in February, the Municipal Corporation reportedly desilted 104 major nallahs and 171 deep drains as part of pre-monsoon preparedness. But beneath the surface of these successes lies a serious and growing menace, encroachment of our nallahs and drainage channels by residents, posing a grave risk to public health, safety, and the environment.

The Municipal Corporation’s officials routinely inspect sites such as Nanak Nagar and Trikuta Nagar to urge residents to remove encroachments and facilitate maintenance. These efforts reflect genuine commitment. During my visit, public signage encouraging cleanliness and good civic behavior had become commonplace. Yet it was equally startling to see that the very nallahs meant to convey rainwater and prevent breeding of disease vectors have been gradually narrowed, obstructed, or entirely blocked.

Encroachment of nallahs isn’t a nuisance, it’s a slow-motion disaster. These aren’t just any drains. Jammu’s natural terrain includes seasonal rivulets, hill-runoff channels, and interconnected nallahs that act as the city’s pressure-release valves during storms. They are our flood defense system. Block them, and you’re welcoming disaster. And disaster has come.

I learned that in recent years, heavy rains have flooded several colonies in Jammu city, not because rainfall increased, but because drainage decreased. In 2023, parts of Digiana and Gangyal were submerged knee-deep. In 2024, Talab Tillo residents posted viral videos of sewage-laced floodwater entering bedrooms. The culprits weren’t hidden, they were visible, in concrete. Houses have been raised on the beds of drains. Shopkeepers have extended platforms over running water. Builders have diverted natural flows with impunity.

This didn’t happen overnight.

Laws were flouted slowly, regularly. The infamous Roshni Act, now scrapped and declared unconstitutional, once enabled the illegal transfer of public land, including water bodies and nallahs, into private hands under the guise of “regularization.” What was public became private. What was essential became invisible.

The Jammu High Court has ordered removal of commercial encroachments, from roadside food stalls to illegal kiosks, but what about residential violations? Who will knock on the doors of those who built their kitchens atop public drains?

Meanwhile, cases of corruption in drainage contracts tell another story. Just this year, the Anti-Corruption Bureau charge-sheeted former officials and contractors for siphoning funds meant for desilting and repair. When money meant to clean nallahs becomes someone’s side income, the result is not just waterlogging, it’s betrayal.

Local media and even social media reports highlight cases where undersized drainage systems, choked by illegal construction or dumping, have led to water logging and flooding in residential localities. Authorities have publicly warned that encroachments have transformed once large nallahs into small drains, severely reducing carrying capacity and exacerbating flood risk during monsoons.

Encroachment of public water channels is no trivial matter. It has multiple cascading consequences: Narrowed and blocked drains cannot handle seasonal rainfall, leading to overflow into streets, houses, and fields. Recurrent flooding is not only an inconvenience, it damages property and livelihoods. Stagnant water becomes a breeding ground for mosquitoes, increasing risks of malaria, dengue, and other vector borne diseases. Garbage and filth in these channels, as documented in areas like Ganderbal, have contributed to serious health and ecological threats in Jammu & Kashmir overall

Encroachment accelerates siltation and pollution, choking wetlands and killing off natural ecosystems over time. Where nallah banks are built over or dumped with waste, neither natural flow nor ecological function remains.

A 2023 civic audit by independent researchers pointed out that Jammu’s drainage network lacks mapping, accountability, and monitoring. Even under Smart City works, drainages are being covered, not cleared. This is in direct contradiction to urban planning best practices.

Reports by the NGO SANDRP and environmental forums have already warned: wetlands and waterbodies in Jammu are choking. Siltation, encroachment, and dumping have been the three-headed monster. And while we worry about rivers, nallahs are dying a quieter death, right beneath our feet.

Walking through sectors of the old city, I saw families extending house boundaries over the nallah edge; in other parts, informal shops and makeshift sheds stood dangerously close to drainage paths. In one neighbourhood, runoff from a blocked nallah had begun seeping into basements and ground floors, eliciting complaints from villagers in a local Facebook group last fortnight.

In planning literature, unplanned urban sprawl and informal construction are widely understood to undermine drainage infrastructure. The catastrophic 2014 floods in Jammu and Kashmir were partly attributed to encroachment of riverbanks, wetlands and canals, development without regard to water courses placed masks over natural drainage, intensifying flood impact.

It is lessons like these that Jammu must heed, lest narrow pockets of encroachment precipitate a larger disaster. Though I applaud the Smart City drive, the risks posed by encroachment demand urgent, coordinated intervention:

Clear delineation of public land reserved for nallahs, drainage, wetlands, and pipe lines. Community awareness campaigns to educate residents on dangers of blocking drains. Strict enforcement under provisions of Jammu & Kashmir’s Irrigation Act (1978), which allows government to prohibit and remove obstructions harming public health or convenience. Regular audits of drainage projects to ensure allocated funds are properly used; recent ACB charges are a wake up call. Resettlement or rehabilitation of encroached residents where feasible, paired with fair compensation or alternative housing, to prevent conflict.

If you’re reading this and think this is someone else’s problem, think again. Encroached nallahs don’t discriminate. They flood everyone. They ruin walls in poor households and foundations in affluent ones. They breed mosquitoes near temples and malls alike. They carry disease, filth, and risk through every ward, every lane, every season.

This is not about pointing fingers. It’s about protecting what still remains.

Jammu stands at a crossroads. The Smart City Initiative offers hope and visible results. Yet the silent threat of encroachment, narrowed nallahs, blocked drains, illegal construction on public land, poses a latent danger.

Flooding, health risks, property damage and environmental decay are not distant futures, they are happening now, in neighbourhoods where drainage lines have been obstructed. Restoring the integrity of nallahs and drainage infrastructure must become as visible a priority as new roads or gardens.

I left Jammu when it was still chaotic, crumbling, yet alive. I return to a smarter city, a better city, but with suffocated lungs. I do not write this in anger. I write this out of love. This city is mine, as it is yours. It is not just a hometown, it is our home. We cannot let it sink under its own silence.

Let no builder be bigger than a river. Let no house be more permanent than a natural flow.Let no citizen say: “It’s not my problem. “It is. It always was.

Let Smart Cities also be Safe cities. Let the next homecoming bring not just pride, but peace.